Art Review – 30 July 2021

British Art Show 9: ‘A Scene At Once Thriving and Struggling To Survive’

Tom Jeffreys

“My thoughts for Art Review on British Art Show 9 – currently at Aberdeen Art Gallery then touring to Wolverhampton, Manchester & Plymouth. Highlights: Kathrin Böhm, Elaine Mitchener, Abigail Reynolds & Hrair Sarkissian.”

The art shown in this survey of contemporary art across the UK – launched at Aberdeen Art Gallery – is by turns powerful and intriguing; the context unavoidably depressing

The pandemic-postponed ninth edition of the British Art Show (BAS9) presents a scene at once thriving and struggling to survive. The exhibition, which normally takes place every five years, was conceived to survey the state of contemporary art across the UK. The art shown in this edition is by turns powerful and intriguing; the context unavoidably depressing. Selected by Hayward Gallery Touring and participating cities (Aberdeen, Wolverhampton, Manchester and Plymouth), the exhibition’s curators, Irene Aristizábal from BALTIC, Gateshead, and Hammad Nasar at Decolonising Arts Institute, University of the Arts London, met with 230 artists and selected 47. Many of them are familiar, some perhaps overfamiliar, but there is also the odd surprise.

While previous editions of BAS have often eschewed overarching themes, Aristizábal and Nasar have three: tactics for togetherness; imagining new futures; and healing, care and reparative history. Loose and overlapping, these inform the curators’ thoughtful accompanying essay but fade into the background across the exhibition. Instead, the visitor proceeds artist by artist from the grandly pillared ground-floor sculpture court, through multiple galleries over three floors and up to a film programme in a dedicated screening room.

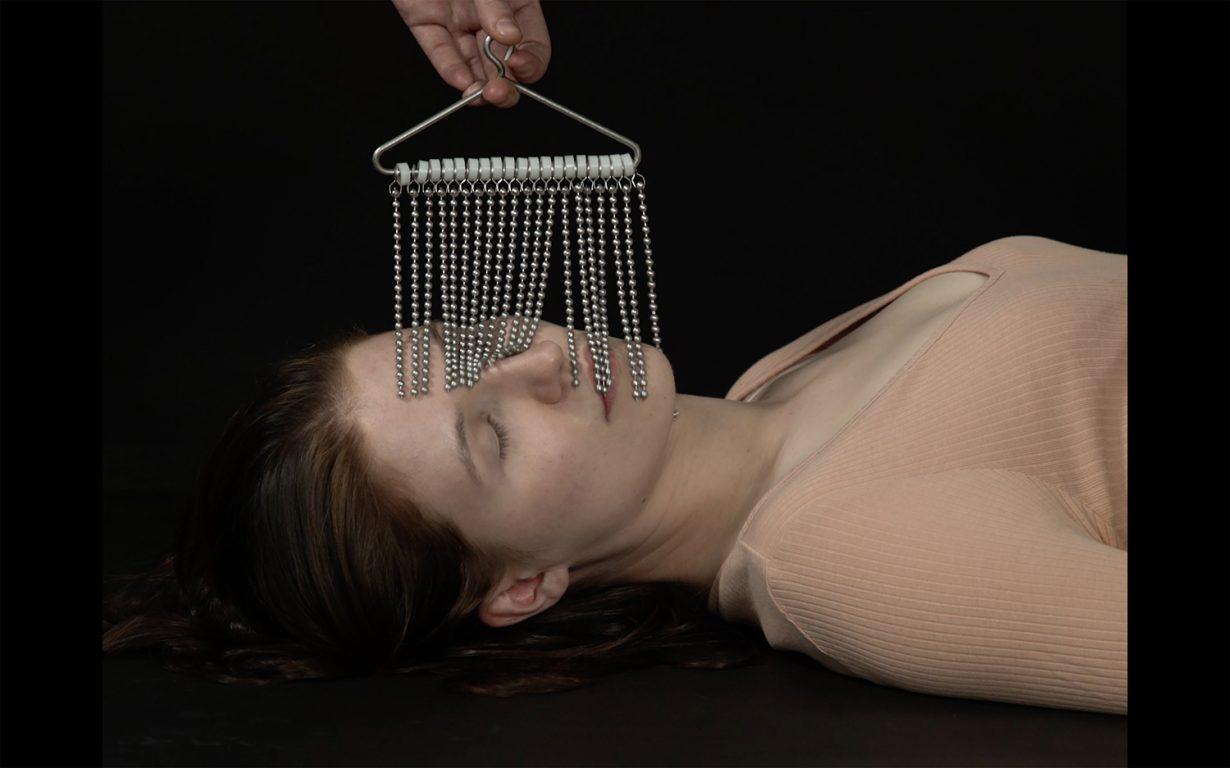

The two most emotionally affecting works are sound installations. Hrair Sarkissian’s Deathscape (2021) is a dark room filled with the scraping sounds of archaeologists unearthing mass graves in Spain dating from the Civil War. With nothing for the eye to settle upon (a bold move for an artist known for photographic work), one is forced to imagine the horrors. Nearby is Elaine Mitchener’s [NAMES II] an evocation (2019–21), which memorialises some of the 2,000 enslaved people owned by a sugar-planter with family in Aberdeenshire. Through overlapping readings, each life is reduced to no more than an imposed English name, a gender and a monetary value.

Aristizábal and Nasar intend for BAS9 to respond to the specific contexts of each host city as it tours the UK. So each iteration will include a different combination of artists and a different thematic lens: alternatives to extractivism in Aberdeen; intersectionality in Wolverhampton; labour conditions and the social contract in Manchester; migration in Plymouth.

This works in some ways – notably through Kathrin Böhm’s When Decisions Become Art (2019–ongoing), which is only showing in Aberdeen. A series of tape drawings and collages, it points to the issues of exhibiting in a gallery funded by oil money while acknowledging the complexities of speaking from afar to a specific context. The work includes an A4 printout, pinned to the wall, which reads: ‘I’m not a local and I don’t know enough about art and oil in Aberdeen, but I know that we all rely on the economies around us, and that we as a human kind can change them if we want to.’ Aberdeen Art Gallery has recently been renovated at a cost of £34.6 million, and its supporters include oil and gas companies BP, CNOOC International and Suncor Energy UK Ltd, as well as The Petroleum Women’s Club of Scotland. This is the hypocrisy Böhm identifies: ‘Artists are tired,’ reads another statement in the work. ‘Tired of organisations who want to show radical ideas without practising them.’

Abigail Reynolds’s Elliptical Reading (2021) is also a highlight – not least for taking visitors outside of the pristine gallery and into the noticeably less lavish Aberdeen Central Library. In some cities (such as Plymouth, 2011) BAS has catalysed collaboration between organisations, but that is less evident here: while millions can be raised for Aberdeen Art Gallery, libraries and vital nonprofits like Peacock Visual Arts remain precarious. The pandemic has limited possibilities for community-driven projects, but Reynolds has engaged library staff and readers across the four host cities. Each has selected a favourite book, which Reynolds has lovingly rebound with marbled paper and graphic depictions of a reader’s hands. They have then been recategorised within the library with a certain flair for mischief. For example, thanks to Aberdeen’s library-events manager, Dallas King, Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991) may now be found in the Business section.

© the artist; courtesy Maureen Paley, London

A survey show like BAS has conflicting priorities: first, selecting the artists, then planning how to exhibit them. The lineup of BAS9 is outstanding, but the exhibition is occasionally unsatisfying. Many artists are presented in isolation; when they are shown together, connections remain unclear or even counterproductive. Intrusively repetitive bouncing and clattering sounds from a looped film by Joanna Piotrowska, for example, make it hard to focus on Anne Hardy’s quietly gorgeous photograms. The works on show are all significant in their own way, but in Aberdeen at least, interesting conversations are not yet developing between them.

British Art Show 9, Aberdeen Art Gallery, 10 July – 10 October, and touring to Wolverhampton, Manchester and Plymouth